It is an enormous honor to deliver this lecture, particularly this year. You have just heard from a number of our profession's luminaries about the monumental effect that Marty Feldstein had on both the world and on their careers. This is personal for me as well, as another of the many students to whom Marty provided such exceptional guidance, support, and investment. Marty has served as a mentor for me throughout my career, from my first week of graduate school through every professional opportunity and decision that I have had, and I am profoundly grateful.

I am privileged to be able to talk with you about one of the many policy arenas that Marty Feldstein helped to shape, from one of his earliest publications, to which this lecture's title alludes. Health system reform is one of the pressing policy issues of the day, and economics has a great deal to contribute to the debate. The economics tool kit is particularly well suited to generating the analytical framework and evidence base needed to inform decisions around the difficult trade-offs inherent to so many aspects of health policy. But, of course, there are a number of challenges to overcome in translating a vast and impressive body of research into policy impact. I will start by trying to define what I mean by "evidence-based health policy" before turning to the current reform debate. I will conclude with thoughts about where, as a profession, we have been more or less successful in achieving that impact and how we might continue to promote the use of the evidence we generate in informing effective policy.

What do I mean by evidence-based health policy? Proponents on both sides of debates often claim to have views grounded in evidence. Having a clear framework for characterizing what we mean by evidence-based health policy is a prerequisite for a rational approach to making policy choices, and may even help focus the debate on the most promising approaches. First, policies need to be well-specified; a slogan is not sufficient. For example, "Medicare for All" isn't really a policy. That slogan masks areas of fundamental disagreement about the role of government and markets, coverage expectations, and cost structure. It may be an effective way to signal a political orientation, but the lack of specificity sidesteps the hard work of assessing the relative effectiveness of the different policies that might fall under that umbrella.

Second, grounding policy decisions in evidence requires a careful distinction between policies and goals. This is important on two fronts: Many different policies may aim to achieve the same goal with very different degrees of effectiveness; and there may be many different goals for a given policy, with different likelihoods of success. For example, consider the financial incentives for physicians to coordinate care. The evidence that this would reduce health care spending — one potential goal — is quite weak, while the evidence that it might improve health outcomes — a different goal — is stronger. Similarly, there may be alternative policies that are more effective in improving health outcomes through coordinating care across sites.

Third, generating the evidence to support policy is an inherently empirical endeavor. Introspection — particularly by economists! — and theory are terrible ways to evaluate policy. For some policies, we have clear conceptual models that suggest the direction of the effect the policy is likely to have, but these models never tell us how big the effect is likely to be. For example, economic theory says that, all else equal, when copayments or deductibles are higher, patients use less care — we're pretty sure that demand slopes down, even for health care — but the theory doesn't tell us by how much. And for other policies, even the direction of the effect is unclear without empirical research, with competing effects potentially going in different directions.

Interpreting the often vast bodies of evidence that speak to a policy question requires judgment and nuance, but it is crucial that interpretation not be flavored by the policy preferences of the researcher or analyst. A given body of evidence can be used to support very different policy positions depending on one's goals — for example, how one weighs costs to taxpayers versus redistribution of health care resources — but different goals shouldn't drive different interpretations of the evidence base.

Translating evidence into policy requires a distinct toolkit. As a profession, economists bring a lot of strengths to the table, and Marty was exceptionally talented and successful in this endeavor. Perhaps one of the discipline's greatest strengths is the very careful and sophisticated approach to causality, eschewing policy prescriptions built on correlations. We also bring a depth of understanding of incentives and markets that helps to highlight potential intended and unintended consequences of policy changes, as well as the static and dynamic effects that those policies have on decision-making. This is also conducive to understanding the ultimate incidence and distributional consequences of different policies. And our analytical framework helps us to interpret evidence in a nuanced way that reflects the complexity of multiple mechanisms at play. Putting this toolkit together is a major asset in generating evidence that remains distinct from advocacy.

There are also substantial weaknesses to contend with. Academics in general are often loath to speak definitively — further study is always needed! We are also not known for the timeliness of our evidence, given lags in data availability, speed of analysis, and publication processes. We struggle both to incorporate real political constraints and to put aside second-order concerns. Lastly, we often do not reward the effort that real translation requires.

This is now playing out in the current health policy debate. Reform efforts have multiple goals, some allocative and some productive. Allocative goals focus on health care availability and affordability across the income distribution — social insurance. Mechanically, this is probably the easier of the two goals, as we have well-developed mechanisms for expanding insurance coverage, albeit with lots of open questions about which are most efficient and what that insurance ought to look like. But it is important to understand the underlying rationale for redistribution through the health care system. It is tempting to think that there are externalities that warrant redistributing resources in this way, for example, that insuring Jim will keep him from spreading disease to me, or that Jim will be so much healthier because of his insurance that his health care use will decline and his earnings and taxes paid will increase enough that I will actually be better off. I don't believe that the evidence supports this. Rather, the primary rationale for publicly funded redistributive insurance plans is altruism. Policy then needs to be based on social preferences for the degree of redistribution. It isn't enough to debate whether "health care is a right." Rather, we need to answer the question: "How much health care for low-income populations do we want to fund with public resources?"

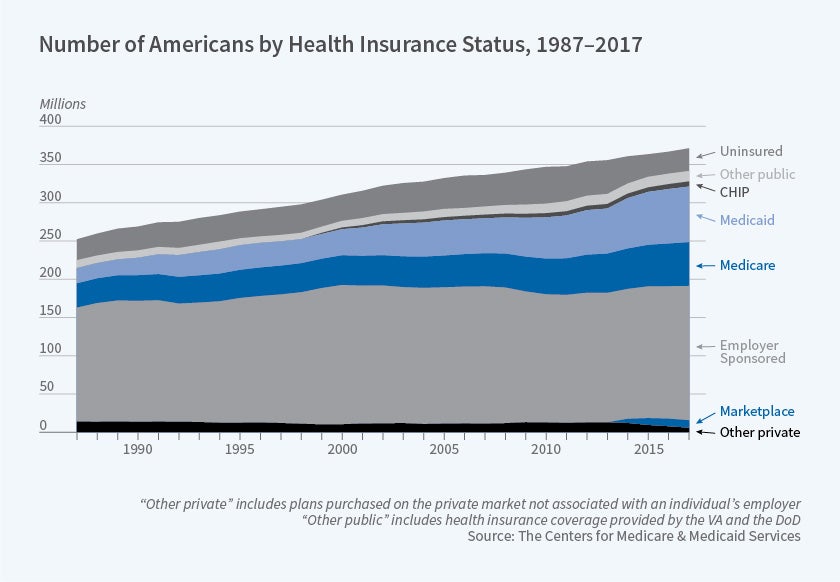

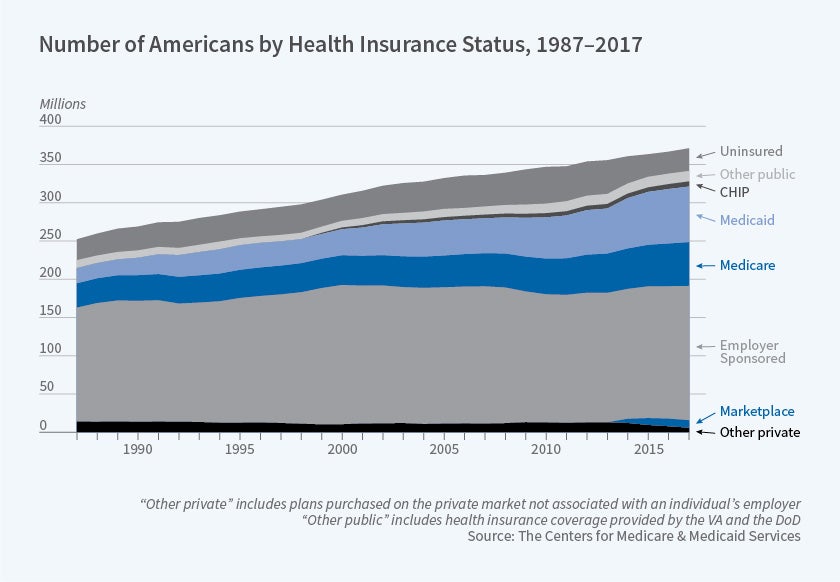

Insurance coverage has substantially expanded since passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA, or Obamacare), but there remain substantial disparities in coverage by, for example, race and ethnicity. It is also worth noting that coverage through new health insurance marketplaces seems to have received attention disproportionate to the share of the population enrolled, with the vast majority of privately insured Americans still obtaining coverage through employer-based plans.

The second goal of improving productive efficiency is even more complex, given the multiple potential policy levers on patient and provider sides as well as the intrinsic imperfections in health care markets. There is little disagreement that we spend a lot of money on health care and that we could be getting more out of our health care system for every dollar that we spend, but that is often where agreement ends. Understanding how we finance health care spending is foundational to understanding the effects of different policy levers, and economic analysis can help focus attention.

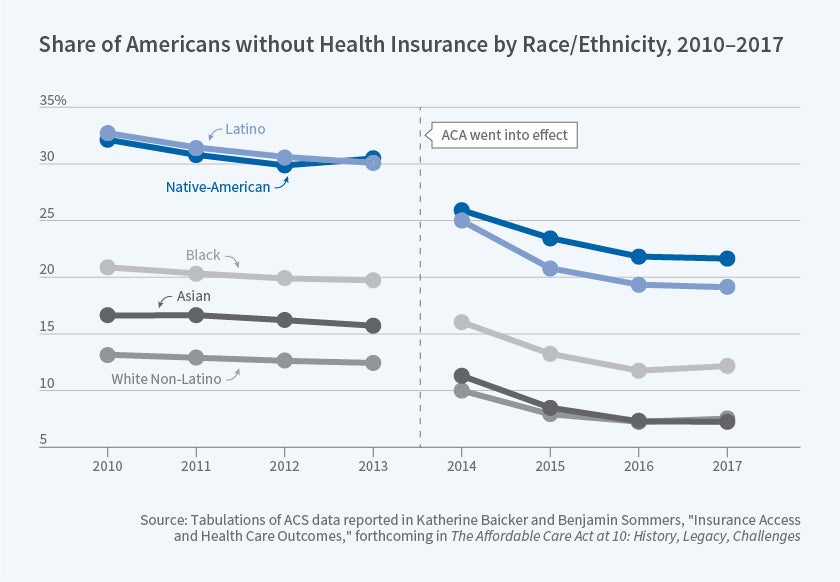

Most care in the United States is purchased through insurance — public or private. Despite mounting concern about cost-sharing, the share of spending that is purchased with out-of-pocket dollars has remained relatively flat, although that masks a change in the composition of those insured by Medicaid with very low cost-sharing and those insured through private plans where higher deductibles are increasingly prevalent. Though public discourse is often not focused on these categories, the majority of health care dollars are spent on physicians and hospitals.

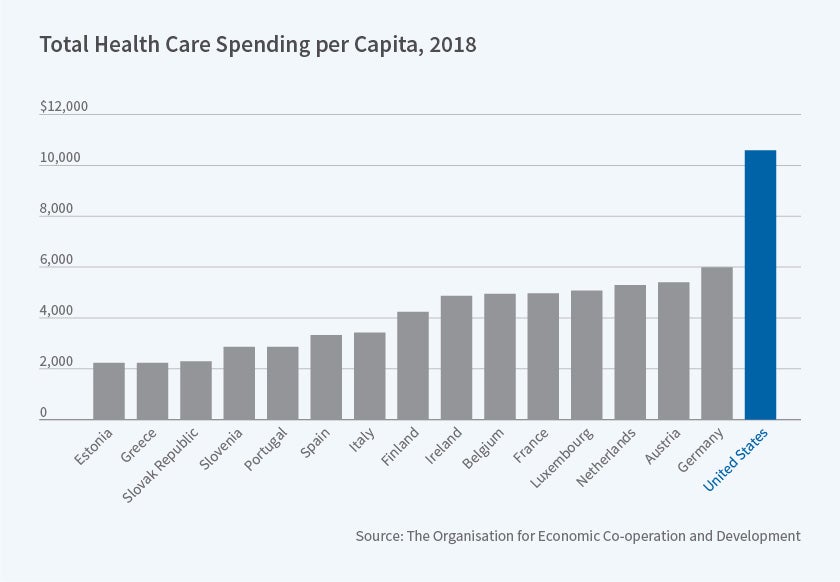

We spend much more on health care than other developed countries, whether in dollars or as a share of GDP, and even once higher income levels are taken into account. There is great interest in understanding the degree to which international differences in spending can be attributed to differences in prices or quantities. This provides an example of the contribution that the economic framework makes. First, such decompositions require better information about quality than is often available, making it difficult to draw apples-to-apples comparisons of quantity. More fundamentally, even if we had such decomposition, we would need to understand the underlying supply and demand conditions that generated the observed price and quantity outcomes. Without that understanding, simply observing higher prices wouldn't indicate the optimal policy response.

Health care value is of course about health outcomes as well as dollars spent. There is ample evidence of inefficiency within our health care system. Here, too, a robust analytical framework is crucial for drawing out policy implications. For example, the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care has produced an important body of evidence on the geographic variation in health care quality and spending even within the Medicare program. This variation is certainly suggestive of underlying inefficiency, and has generated a fruitful line of research into the underlying causes of that variation. But the variation alone does not tell us how policy ought to be different, and the goal of policy ought to be improving system efficiency, rather than dampening variation per se.

With multiple factors beyond the health care system determining health outcomes, it is challenging to generate evidence about the health effects of additional spending, but this is where our toolkit can add the greatest value to the debate. I will start on the patient side with the effects of expanding health insurance coverage and of the features of those health insurance plans.

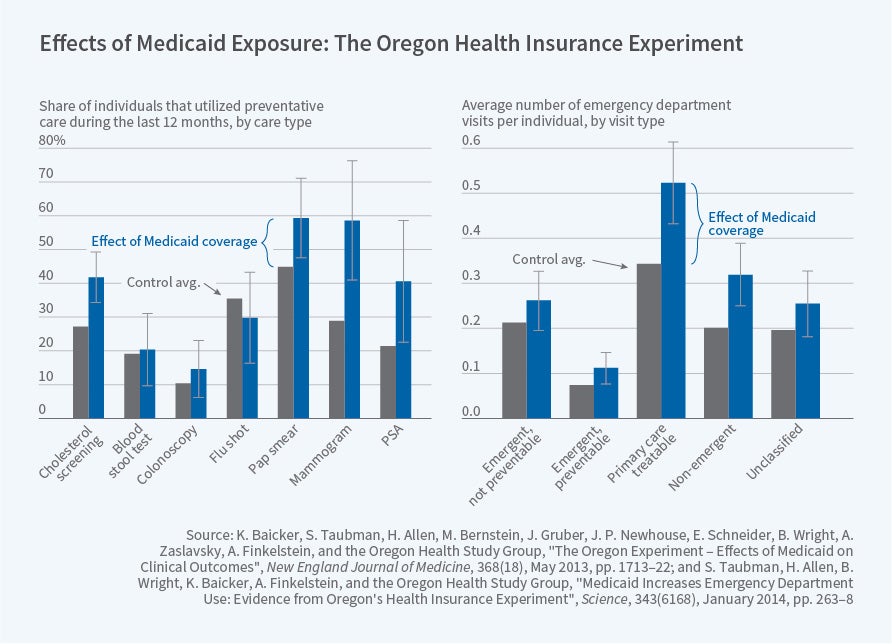

The primary increase in coverage generated by the ACA/Obamacare was through Medicaid. This raises the first-order question of what Medicaid coverage actually does. This is a prime example of theory highlighting competing effects on both the cost and benefit sides. The primary cost of expanding insurance is increased health care use. To non-economists this may sound more like the point rather than a cost, but achieving the same health while expending fewer health care resources would be a good thing. Insurance lowers the price of health care, which should increase health care use, but many proponents of expansion hoped that having insurance would reduce patients' spending by moving them out of expensive emergency departments and into more cost-effective primary care. On the benefits side, there are multiple potential benefits of insurance expansion. Insurance ought to provide greater financial security, often underappreciated in the debate. But it's possible that the uninsured had fewer opportunities to spend money on health care. Of course, the main potential benefit is improved health — although in theory, insurance could undermine enrollees' incentives to maintain their health (though this seems unlikely). Empirical evidence is thus needed on all fronts.

These effects are notoriously difficult to estimate, because people who are covered by Medicaid are different from the uninsured in many ways — such as income and underlying health — that may confound estimates. Along with colleagues, Amy Finkelstein and I had the chance to estimate these effects using the rigor of a randomized controlled trial. In 2008, Oregon had a waiting list for its Medicaid program for non-disabled low-income adults, a population that was optional for states to cover, and which only a minority of states did at the time. The state drew names from the list by lottery, giving us a remarkable opportunity to gauge Medicaid's effects. We found that Medicaid increased health care use across settings, including primary care, prescription drugs, hospitals, and — surprisingly to many — emergency departments. This result is actually not surprising based on economics principles. As noted, demand slopes down, even for health care, and insurance dramatically lowers the price for emergency department care. Of course, insurance also lowers the price of primary care, and if the doctor and the emergency department are strong substitutes, this cross-price elasticity could dominate the own-price elasticity and drive emergency department use down on net. But it is not surprising — at least to economists and, it turns out, many physicians — that the own-price elasticity dominates. We also found that financial security was substantially improved by having Medicaid. The effects on health were much more nuanced. People reported that their health was much better, and rates of depression were dramatically lower, but we didn't detect any improvements in blood pressure, cholesterol, blood sugar, or obesity. These results require careful, measured interpretation. I'll return to how that worked out for us in the popular press.

The next question is how patient cost-sharing and the other features of insurance plans affect health care use and efficiency. Classical theory suggests that optimal cost-sharing ought to balance insurance protection against moral hazard. The insurance plans that we observe in both the public and private sectors look far from optimal. On the public side, Medicare alone provides surprisingly limited coverage, leaving beneficiaries exposed to unlimited catastrophic out-of-pocket spending, motivating almost all Medicare beneficiaries to have wrap-around Medigap coverage that virtually eliminates cost-sharing as a tool to modulate utilization.

On the private side, the dominance of the employer-sponsored insurance market is driven in large part by the tax preference for health insurance benefits relative to wage compensation, which also drives down cost-sharing, since care covered through insurance plan premiums is often tax-preferred to out-of-pocket spending. This aspect of the tax code is thus both inefficient (driving inefficient utilization through moral hazard) and regressive (favoring people with higher incomes and more generous benefits) — a rare opportunity to improve both efficiency and distribution through reform.

This is a prime example of the challenge of translating economic insights into policy: Even though economists on both sides of the aisle agreed, proposing the taxation of employer-sponsored insurance to policymakers and the public was not popular. The "Cadillac tax" on expensive plans came into existence largely because it was nominally levied on insurers rather than taxpayers. This made it more politically palatable, even though it does not mean that the ultimate incidence falls on insurers, and it constrains the degree to which it can undo the regressivity of the tax treatment of employer-sponsored insurance. Earlier this year, the House voted to repeal the Cadillac tax; whether it will ever take effect remains an open question.

This points to opportunities to improve efficiency using patient-side levers. A large body of research points to potential innovations in insurance design through greater use of cost-sharing, often misperceived as just shifting costs to patients rather than as a tool to reduce low-value care; taxing of Medigap benefits; and shared-savings models. But a growing body of evidence also highlights the limitations of the traditional rational agent model. Patients often react to copays in ways that are inconsistent with the model. We see not only overutilization, but underutilization of high-value care — such as limited adherence to high-value drugs. And even small copays seem to dissuade use of care with substantial health benefits. Thus, insurance design that takes this "behavioral hazard" as well as traditional moral hazard into account has the potential to improve efficiency while maintaining insurance protection.

Providers are human beings who are sensitive to both prices and behavioral forces, and much of our health care is delivered through payment models that promote higher-volume, rather than higher-value, use of care. Medicare payments have an outsized effect on the system.

There are also multiple opportunities to improve payments on the provider side. Providers are human beings who are sensitive to both prices and behavioral forces, and much of our health care is delivered through payment models that promote higher-volume, rather than higher-value, use of care. Medicare payments have an outsized effect on the system, driving investment in expensive technologies and setting norms for coverage and standards of care. Most Medicare beneficiaries remain in the standard fee-for-service Medicare model, but there is experimentation with alternative models. The "sustainable growth rate" formula provides a cautionary tale — for another day — of unintended consequences of global price setting. Accountable Care Organizations have been set up to share savings from more efficient delivery with providers, but with limited incentives that seem to have led to limited effects. Bundled payments hold the promise of constraining spending per procedure, but without addressing the number of procedures.

There are also a host of questions about policy mechanisms for addressing market imperfections, such as far-from-perfect competition and limited information on quality for patients. There is some inherent tension between policies that rely on competition to drive down prices and premiums and drive up quality with those that rely on coordination across providers and sites to improve efficiency of delivery and quality of care. And each of these can have crucial dynamic effects, driving the return to entry, innovation, and investment in improved delivery.

I would like to conclude by returning to the question of how successful we have been — and how we can be more successful — in promoting the use of our scholarship and evidence in informing health policy. The Oregon results highlight some of the challenges. In the days after our nuanced findings on the effects of Medicaid on physical health were published, newspaper headlines were all over the map, some suggesting that we had proven that Medicaid was a terrible program and others suggesting that we had proven its high value. One even acknowledged that the results were being used to further entrenched ideological views. One might find this discouraging, but in fact many policymakers were open to learning more about the findings, and it became much harder to support either the unduly optimistic view of the program, that it would improve health and the efficiency of delivery so much that it would save money, and the unduly pessimistic view that people on the program were no better off than if they were uninsured. And, of course, there are many, many other studies that speak to these important points.

There are some notable successes in the dissemination of evidence into policy, from congressional testimony to judicial citations and even to law. But success depends on devoting substantial time and energy to timely translation of our results into outlets and formats that are accessible to those in a position to act on them.

This is an edited version of the Martin Feldstein Lecture delivered on July 25, 2019, at the NBER Summer Institute.