John Dickinson and other moderates debated whether war with Britain outweighed the real benefits colonists enjoyed as subjects of the king.

by Jack Rakove 6/3/2010 6/26/2023

Fearing that American independence from Britain would fuel a fight with allied European nations, John Dickinson refused to sign the Declaration of Independence.

In the decade before the American colonies declared independence, no patriot enjoyed greater renown than John Dickinson.

In 1765, he helped lead opposition to the Stamp Act, Britain’s first effort to get colonists to cover part of the mounting cost of empire through taxes on paper and printed materials.

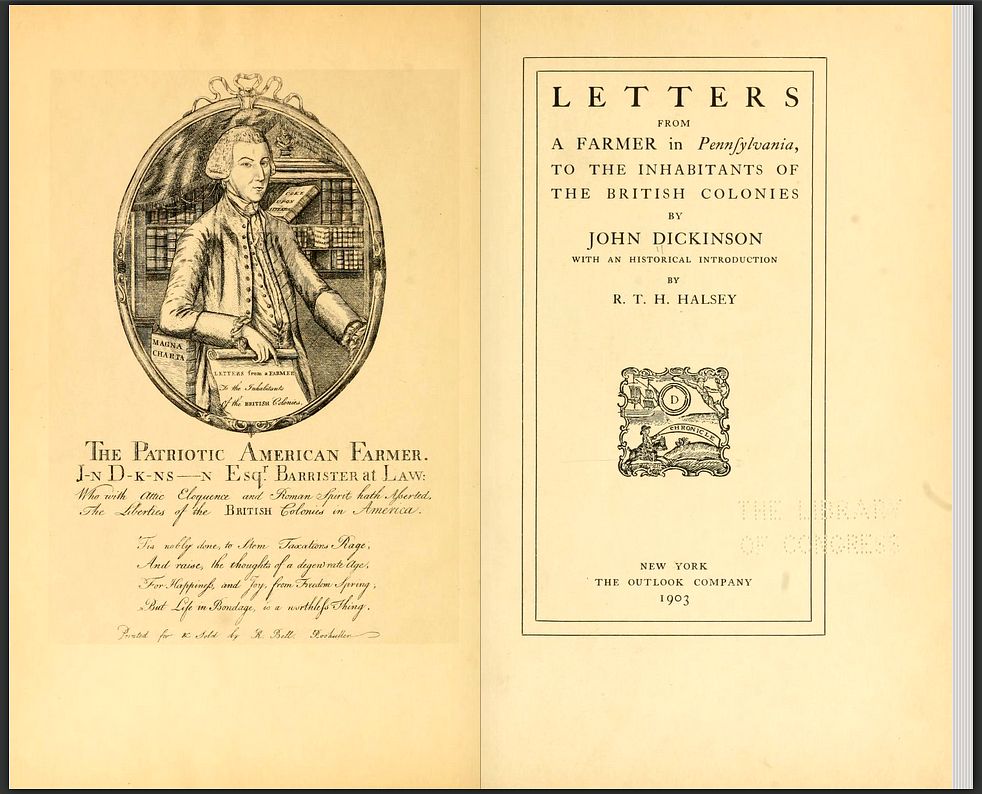

Then, after Parliament rescinded the Stamp Act but levied a new set of taxes on paint, paper, lead and tea with the Townshend Duties of 1767, Dickinson galvanized colonial resistance by penning Letters From a Pennsylvania Farmer, a series of impassioned broadsides widely read on both sides of the Atlantic. He even set his political sentiments to music, borrowing the melody from a popular Royal Navy chantey for his stirring “Liberty Song,” which included the refrain: “Not as slaves, but as freemen our money we’ll give.”

Yet on July 1, 1776, as his colleagues in the Continental Congress prepared to declare independence from Britain, Dickinson offered a resounding dissent.

Deathly pale and thin as a rail, the celebrated Pennsylvania Farmer chided his fellow delegates for daring to “brave the storm in a skiff made of paper.” He argued that France and Spain might be tempted to attack rather than support an independent American nation. He also noted that many differences among the colonies had yet to be resolved and could lead to civil war.

When Congress adopted a nearly unanimous resolution the next day to sever ties with Britain, Dickinson abstained from the vote, knowing full well that he had delivered “the finishing Blow to my once too great, and my Integrity considered, now too diminish’d Popularity.”

Indeed, following his refusal to support and sign the Declaration of Independence, Dickinson fell into political eclipse. And some 200 years later, the key role he played in American resistance as the leader of a bloc of moderates who favored reconciliation rather than confrontation with Britain well into 1776 is largely forgotten or misunderstood.

To be a moderate on the eve of the American Revolution did not mean simply occupying some midpoint on a political line, while extremists on either side railed against each other in frenzied passion. Moderation for Dickinson and other members of the founding generation was an attitude in its own right, a way of thinking coolly and analytically about difficult political choices. The key decision that moderates ultimately faced was whether the dangers of going to war against Britain outweighed all the real benefits they understood colonists would still enjoy should they remain the king’s loyal subjects.

Dickinson and his moderate cohorts were prudent men of property, rather than creatures of politics and ideology. Unlike the strong-willed distant cousins who were leaders of the patriot resistance in Massachusetts—John and Samuel Adams—moderates were not inclined to suspect that the British government was in the hands of liberty-abhorring conspirators. Instead, they held out hope well into 1776 that their brethren across the Atlantic would come to their senses and realize that any effort to rule the colonies by force, or to deny colonists their due rights of self-government, was doomed to failure. They were also the kind of men British officials believed would choose the benefits of empire over sympathy for suffering Massachusetts; the colony that King George III; his chief minister, Lord North and a docile Parliament set out to punish after the Boston Tea Party of December 1773. Just as the British expected the Coercive Acts that Parliament directed against Massachusetts in 1774 would teach the other colonies the costs of defying the empire, so they assumed that sober men of property, with a lot at stake, would never endorse the hot-headed proceedings of the mob in Boston. Yet in practice, exactly the opposite happened. Dickinson and other moderates ultimately proved they were true patriots intent on vindicating American rights.

Men of moderate views could be found throughout America. But in terms of the politics of resistance, the heartland of moderation lay in the middle colonies of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Maryland. Unlike Massachusetts, where a single ethnic group of English descent predominated and religious differences were still confined within the Calvinist tradition, the middle colonies were a diverse melting pot where differences in religion, ethnicity and language heightened the potential for social unrest. This was also the region where a modern vision of economic development that depended on attracting free immigrants and harnessing their productive energy shaped the political view of moderate leaders. Let Samuel Adams indulge his quaint notion of turning the town of Boston into “the Christian Sparta.” The wealthy landowners of the middle colonies, as well as the merchant entrepreneurs in the bustling ports of Philadelphia, New York, Annapolis and Baltimore, knew that the small joys and comforts of consumption fit the American temperament better than Spartan self-denial and that British capital could help fund many a venture from which well-placed Americans could derive a healthy profit.

Dickinson, the son of a land baron whose estate included 12,000 acres in Maryland and Delaware, studied law at the Inns of Court of London as a young man in the 1750s. An early trip to the House of Lords left him distinctly unimpressed. The nobility, he scoffed in a letter to his parents, “drest in their common cloths” and looked to be “the most ordinary men I have ever faced.” When Thomas Penn, the proprietor of Pennsylvania, took him to St. James for a royal birthday celebration, Dickinson was struck by the banal embarrassment King George II showed, staring at his feet and mumbling polite greetings to his guests. Yet Dickinson’s memory of his sojourn in cosmopolitan London laid a foundation for his lasting commitment to reconciliation on the eve of the Revolution. Whatever the social differences between the colonies and the mother country, England was a dynamic, expanding and intellectually creative society. Like many moderates in the mid-1770s, Dickinson believed that the surest road to American prosperity lay in a continued alliance with the great empire of the Atlantic.

Another source of Dickinson’s moderation lay in his complicated relation to the Quaker faith. Dickinson’s parents were both Quakers and so was his wife, Mary Norris, the daughter and heiress of a wealthy Pennsylvania merchant and landowner. Dickinson balked at actively identifying with the Friends and their commitment to pacifism. Even though he worried as much as any moderate about resistance escalating to all-out warfare, he supported the militant measures Congress began pursuing once the British military clampdown began in earnest. But at the same time, Dickinson’s rearing and close involvement with Quaker culture left him with an ingrained sense of his moral duty to seek a peaceful solution to the conflict.

Dickinson’s belief that the colonists should make every feasible effort at negotiation was reinforced by his doubts as to whether a harmonious American nation could ever be built on the foundation of opposition to British misrule. Remove the superintending authority of empire, Dickinson worried, and Americans would quickly fall into internecine conflicts of their own.

General outrage swept through the colonies after the British closed the port of Boston in May 1774. When the First Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia in September in response to the crisis, John and Samuel Adams immediately began courting Dickinson, whose writings as the Pennsylvania Farmer made him one of the few men renowned across the colonies. At their first meeting, John Adams wrote in his diary, Dickinson arrived in “his coach with four beautiful horses” and “Gave us some Account of his late ill Health and his present Gout….He is a Shadow—tall, but slender as a Reed—pale as ashes. One would think at first Sight that he could not live a Month. Yet upon a more attentive Inspection, he looks as if the Springs of Life were strong enough to last many Years.” Dickinson threw his support behind a compact among the colonies to boycott British goods, but by the time the Congress ended in late October, Adams was growing exasperated with his sense of moderation. “Mr. Dickinson is very modest, delicate, and timid,” Adams wrote.

Dickinson and other moderates shared an underlying belief with more radical patriots that the colonists’ claims to be immune from the control of Parliament rested on vital principles of self-government. Even if Boston had gone too far with its tea party, the essential American pleas were just. But the moderates also desperately hoped that the situation in Massachusetts would not spin out of control before the government in London had a fair opportunity to gauge the depth of American resistance and respond to the protests Congress submitted to the Crown.

That commitment to conciliation was sorely tested after fighting broke out at Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775.

“What human Policy can divine the Prudence of precipitating Us into these shocking Scenes,” Dickinson wrote to Arthur Lee, the younger, London-based brother of Richard Henry Lee of Virginia. “Why have we been so rashly declared Rebels?” Why had General Thomas Gage, the royal governor of Massachusetts, not waited “till the sense of another Congress could be collected?” Some members were already resolved “to have strain’d every nerve of that Meeting, to attempt bringing the unhappy Dispute to Terms of Accommodation,” he observed. “But what Topicks of Reconciliation” could they now propose to their countrymen, what “Reason to hope that those Ministers & Representatives will not be supported throughout the Tragedy as They have been thro the first Act?”

Dickinson’s despair was one mark of the raw emotions triggered throughout the colonies as the news of war spread. Another was the tumultuous reception that the Massachusetts delegates to the Second Continental Congress enjoyed en route to Philadelphia in early May. The welcome they received in New York amazed John Hancock, the delegation’s newest member, to the point of embarrassment. “Persons appearing with proper Harnesses insisted upon taking out my Horses and Dragging me into and through the City,” he wrote. Meanwhile no matter what direction delegations from other colonies took as they headed to Philadelphia, they were hailed by well-turned-out contingents of militia. The rampant martial fervor of the spring of 1775 reflected a groundswell of opinion that Britain had provoked the eruption in Massachusetts and Americans could not flinch from the consequences.

Military preparations became the first task of the new session of Congress, and a week passed before any attempts to negotiate with the British were discussed. Many delegates felt that the time for reconciliation had already passed. The king and his ministers had received an “olive branch” petition from the First Congress and ignored it. Dickinson delivered a heartfelt speech in which he acknowledged that the colonists must “prepare vigorously for War,” but argued that they still owed the mother country another chance. “We have not yet tasted deeply of that bitter Cup called the Fortunes of War,” he said. Any number of events, from battlefield reverses to the disillusion that would come to a “peaceable People jaded out with the tedium of Civil Discords” could eventually tear the colonies apart.

Dickinson and other moderates prevailed on a reluctant Congress to draft a second olive branch petition to George III. The debate, recorded only in the diary of Silas Deane of Connecticut, was heated. Dickinson insisted not only that Congress should petition anew, but that it should also send a delegation to London, authorized to initiate negotiations. Dickinson’s plans were attacked “with spirit” by Thomas Mifflin of Pennsylvania and Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, and dismissed with “utmost contempt” by John Rutledge of South Carolina, who declared that “Lord North has given Us his Ultimatum, with which We cannot agree.” At one point tempers rose so high that half of Congress walked out.

In the end, the mission idea was rejected, but Congress did agree to a second olive branch petition for the sake of unity, which, John Adams and others sneered, was an exercise in futility.

Over the next two months, Congress took a series of steps that effectively committed the colonies to war.

In mid-June, it began the process of transforming the provisional forces outside Boston into the Continental Army to be led by George Washington. Washington and his entourage left for Boston on June 23, having learned the day before of the carnage at the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17. Meanwhile, John Adams chafed at the moderates’ diversionary measures. His frustration came to a boil in late July. “A certain great Fortune and piddling Genius whose Fame has been trumpeted so loudly has given a silly Cast to our whole Doings,” he grumbled in a letter to James Warren, president of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress. Adams obviously meant Dickinson, and he then went on to complain that “the Farmer’s” insistence on a second petition to the king was retarding other measures Congress should be taking. But a British patrol vessel intercepted the letter and sent it on to Boston, where General Gage was all too happy to publish it and enjoy the embarrassment it caused.

Adams received his comeuppance when Congress reconvened in September 1775. Walking to the State House in the morning, he encountered Dickinson on the street.

“We met, and passed near enough to touch Elbows,” John wrote to his wife, Abigail, back home. “He passed without moving his Hat, or Head and Hand. I bowed and pulled off my Hat. He passed haughtily by. The Cause of his Offence, is the Letter no doubt which Gage has printed.”

Adams was loath to admit that his original letter to Warren had been as unfair in its judgment as it was ill-advised in its shipment. Dickinson sincerely thought a second petition was necessary, not only to give the British government a last chance to relent, but also to convince Americans that their Congress was acting prudently.

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Thank you for subscribing!Having pushed so hard to give peace a chance, Dickinson felt equally obliged to honor his other commitment to “prepare vigourously for War.” He joined Thomas Jefferson, a newly arrived Virginia delegate, in drafting the Declaration of the Causes and Necessity for Taking up Arms, which Washington was instructed to publish upon his arrival in Boston. Meanwhile Dickinson undertook another ploy to try to slow the mobilization for war. He wrote a set of resolutions, which the Pennsylvania legislature adopted, barring its delegates from approving a vote for independence. The instructions were a barrier to separation, but only so long as many Americans throughout the colonies hesitated to take the final step.

That reluctance began to crack after Thomas Paine published Common Sense in January 1776. Paine’s flair for the well-turned phrase is exemplified in his wry rejoinder to the claim that America still needed British protection: “Small islands not capable of protecting themselves, are the proper objects for kingdoms to take under their care, but there is something very absurd, in supposing a continent to be perpetually governed by an island.” Public support for more radical action was further kindled as Britain indicated that repression was the only policy it would pursue. Township and county meetings across the country adopted pro-independence resolutions that began flowing into Congress, as John Adams remarked, “like a torrent.” In May 1776, Adams and other delegates moved to break the logjam in Pennsylvania by instructing the colonies to form new governments, drawing their authority directly from the people. Soon the authority of the Pennsylvania legislature collapsed, and the instructions Dickinson had drawn lost their political force.

In the weeks leading up to the vote on independence, Dickinson chaired the committee that Congress appointed to draft Articles of Confederation for a new republican government. Meanwhile, he remained the last major foe of separation. Other moderates, like Robert Morris of Pennsylvania and John Jay of New York, also had hoped that independence could be postponed. Yet having grown increasingly disenchanted with Britain’s intransigence, they accepted the congressional consensus and redoubled their commitment to active participation in “the cause.”

Only Dickinson went his own way. Perhaps his Quaker upbringing left him with a strong conscience that prevented him from endorsing the decision that others now found inevitable. Perhaps his youthful memories of England still swayed him. In either case, conscience and political judgment led him to resist independence at the final moment, and to surrender the celebrity and influence he had enjoyed over the past decade.

Pennsylvania’s new government quickly dismissed Dickinson from the congressional delegation. In the months that followed, he took command of a Pennsylvania militia battalion and led it to camp at Elizabethtown, N.J. But Dickinson had become an opportune target of criticism for the radicals who now dominated Pennsylvania politics. When they got hold of a letter he had written advising his brother Philemon, a general of the Delaware militia, not to accept Continental money, their campaign became a near vendetta against the state’s once eminent leader. Dickinson protested that he meant only that Philemon should not keep money in the field, but in the political upheaval of 1776 and 1777, the fiercely independent Dickinson was left with few allies who could help him salvage his reputation.

Eventually Dickinson returned to public life. In January 1779, he was appointed a delegate for Delaware to the Continental Congress, where he signed the final version of the Articles of Confederation he had drafted. He subsequently served as president of the Delaware General Assembly for two years before returning to the fray in Pennsylvania, where he was elected president of the Supreme Executive Council and General Assembly in November 1782. He was also a delegate to the Constitutional Convention in 1787 and promoted the resulting framework for the young republic in a series of essays written under the pen name Fabius.

Despite his accomplishments late in life, Dickinson never fully escaped the stigma of his opposition to independence. But upon hearing of Dickinson’s death in February 1808, Thomas Jefferson, for one, penned a glowing tribute: “A more estimable man, or truer patriot, could not have left us,” Jefferson wrote. “Among the first of the advocates for the rights of his country when assailed by Great Britain, he continued to the last the orthodox advocate of the true principles of our new government, and his name will be consecrated in history as one of the great worthies of the Revolution.”

A few years later, even John Adams sounded a note of admiration for his erst-while adversary in a letter to Jefferson.

“There was a little Aristocracy, among Us, of Talents and Letters,” Adams wrote. “Mr. Dickinson was primus inter pares”—first among equals.

Historian Jack Rakove won a Pulitzer Prize for Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution. His most recent book is Revolutionaries: A New History of the Invention of America.

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.